Note: This article fulfills the requirements of the “Research Blog Post” for ENGL 602 Methods and Materials Research, Liberty University, English PhD.

So, you want to write historical fiction. Congratulations! You have accomplished the first step when deciding to write a book—determining the genre of your novel. Most novel writing requires at least a little bit of research. What are the train schedules for a northbound train leaving London? What are the particular symptoms of an illness I want my character to have? How does one go about hiding a dead body….you get the picture. But historical fiction requires a great deal more research than the average book. Historical fiction is based on facts, usually real people, places or events, and although it is still fiction, your reader will want—and expect—the facts to be accurate. Nothing throws a reader off more than putting potatoes on the dinner plate of a 15th century lord in England, when potatoes didn’t arrive in Europe until the mid- 16th century. (The horror!)

As silly as that sounds, it is painfully true. Historical fiction readers expect authors to have done their research and not add things to their fiction that pulls the reader out of time and place when they are fully immerged in an intriguing historical tale. It is up to the writer to make sure they have done their research so as not to upset the flow of the story.

How Do I Know What I Need to Research?

One of the easiest things to do when researching information for a story is to fall down the proverbial rabbit hole. Sometimes getting caught up in all the little historical details may not add to the overall plot and might feel like a waste of time. Yet, the information uncovered in these “rabbit holes” can add another layer of authenticity to the story and make the reader feel right at home in the setting that you are creating for them.

If you are not sure where to begin your research, start with the main points of the story. When did the events happen? Who are the characters involved? I also like to research the political climate. Who was the ruler during the period I am writing about? Was it a king or queen? A dictator? A president? The political and religious atmosphere at the time of your story can make a difference on how the story unfolds.

Once you have established the timeframe then you can move on to the smaller details. It might be wise to make a list of things that have changed over the centuries. Read over your story and ask yourself if the details you are giving are modern. When were they invented? How did the characters dress? Did they eat those kinds of foods? Did they use the vernacular that you are using in your storytelling? This could become quite an exhaustive list, but it can be narrowed down substantially by asking yourself what makes a good historical setting? The food? The clothing? The innovations? Or perhaps it is the facts surrounding the event that you are writing about or the place where the events occurred. Whatever stands out to you as making the most authentic story, focus on those things.

The political and religious atmosphere at the time of your story can make a difference on how the story unfolds.

If you are writing about real historical events or people, that adds another element of accuracy that leaves little room for error. Even though historical fiction readers must keep in mind that the story is fiction, they expect the events and characters to be accurately portrayed unless an author’s note at the end explains why they have deviated from the true story.

Where Do I Find the Information I Need?

Now that you’ve narrowed down what you need to research, you need to figure out where to find the information you need. Biographies and non-fiction history books are a great place to start. In fact, you may have already read a biography or other historical account which in turn inspired the story you now want to write. However, it is not always affordable to purchase all the books you need in order to get the information you seek. Also, libraries do not always have the books you need, especially if you live in rural areas where the town libraries are not well-stocked. Interlibrary loans, a service that allows patrons to borrow books from libraries outside of their local library are a possibility, if you have the time to wait for the materials to arrive. However, many books can be accessed online, either in eBook form or on publications sites such as Project Gutenberg. Depending on how old the book is, another great site is archive.org. This site has the published book, scanned and posted, and you can flip through the pages of the book as if you were actually turning the pages. There are great search options too, which makes it easier to look for specific information.

Academic sites such as JSTOR are also a great resource when researching historical information. They are especially useful if you are looking for primary sources in which you need information directly from the time period or event you are researching. However, these online libraries are usually not available to the general public without an affiliation with a university or other academic association. Some periodicals and other online journals such as The Historical Journal or History Today, also provide information. Sometimes there is a small fee charged, and some are free.

Another great resource is the historical blog. Historians, whether scholarly or armchair, provide useful information in the form of research that has already been done for you. Many blogs also post their bibliography or works cited, which can give you more information for your research. However, random blog sites can run the risk of inaccurate information if the blogger has not done careful research.

In her article, “Autobiography of an Archivist,” Nan Johnson speaks of finding material of use where she least expected it, such as old textbooks, speeches, essays, even annotations in college catalogues. Information on your topic can be found in a myriad of different places, you only need to start looking for it. Travelling to the places you are writing about (if possible), trips to the museum or even speaking with reenactment actors, can all be a means of gathering information about your historical characters and events.

How Do I Know if a Source is Credible and Appropriate for My Project?

As a general rule, historical information in the form of biographies and other non-fiction books can be counted on for the accuracy of information. These books contain bibliographies and utilize footnotes and endnotes to give the reader an idea of where the information came from.

However, as with other fields of study, at times historians can be one-sided in their telling of history. Unfortunately, sometimes the old cliché still rings true: history is written by the victors. Cultural, racial, and gender biases can occur and the information might be shared through the lens of a bygone era in which we cannot relate. These texts must be read with an understanding of the author’s viewpoint and how that viewpoint affects the information being shared.

When gleaning information from blogs and other informational sites online, careful consideration must be given to the truthfulness of information. When possible, check the author’s sources to verify accuracy by looking for the use of bibliographies and other links to see where the author obtained their information.

You also want to make sure the site is an appropriate source for the information you are taking from it. The information being provided from the chosen site should be well-researched and provided, to a certain extent, without bias.

Other valuable resources for historical information are documentaries and historical dramas. However, researchers must keep in mind that a lot of creative license is taken when filming historical pieces. It might be good for inspiration, but dramas should not be relied upon for historical accuracy. Documentaries would be a more appropriate choice if the information is coming from a reliable historian or other dependable researcher. However, documentaries are also not appropriate sources when researching clothing styles of particular eras, as the purpose of the documentary is usually to inform on events and people and not necessarily the clothing of the period.

How Do I Incorporate Sources into My Writing?

When writing historical fiction, it is generally not required to give references or cite sources, as the story is in fact fictional. Most fictional works print disclaimers at the beginning of the book, indicating that any information written in the story pertaining to real people is fictional and should be treated as such. However, many authors like to include historical notes in the back of the book, elaborating on the facts they used to create their story. If a certain historian’s viewpoint or information was used to perpetuate a certain idea concerning the characters or events, this would be the appropriate place to reference those sources. In her article, Creating Cromwell, Anne-Marie Harvatt explains, “How much attention the authors of historical novels give to theory varies, but their interviews, paratextual material, and metafictional commentary (self-referential and self-conscious commentaries within the text) suggest an awareness of the subjectivity of both their sources and novels, alongside a feeling of responsibility to the facts and a desire to justify their treatment of those facts.” Incorporating historical facts into the fictional story is what historical fiction is all about, and a good writer can create an accurate story with only a partial truth.

Where Can I Find More Information?

Nan Johnson’s article, Autobiography of an Archivist, explains the many different ways she gathered information for her book, Nineteenth Century Rhetoric in North America. It is an excellent source for learning to view the media that we come in contact with every day, and how to look at the information surrounding us in order to use it for writing purposes. Her article can be accessed here.

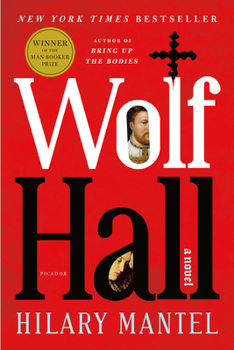

Anne-Marie Harvatt’s article, “Creating Cromwell: An Aanalysis of the Historical Novel’s Position and Potentiality Through a Study of Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall Trilogy,” is an excellent source that discusses the role historical fiction plays in interpreting history and conveying historiography. It can be accessed here.

Works Cited:

Harvatt, Anne-Marie. “Creating Cromwell: an analysis of the historical novel’s position and potentiality through a study of Hilary

Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy”. Rethinking History, vol 28, no. 1, 5 Dec. 2023, pp. 70–87.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13642529.2023.2274773

Johnson, Nan. “Autobiography of an Archivist.” Working in the Archives : Practical Research Methods for Rhetoric and Composition,

Southern Illinois University Press, 2009, pp. 290–299, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/liberty/reader.action?